Extracting reference metadata using hidden Markov models and Viterbi algorithm

Recently, a friend of mine contacted me asking help to accomplish an unusual task – extract all references contained in PDF files and convert them into machine-friendly format. PDFs in question were all kinds of academic papers and publications. Typical reference looked like this:

Rakishev B.R. Open Cast Mining in Kazakhstan Under Market Conditions.

//The 21st World Mining Congress & Expo 2008. New Challenges and Visions for

Mining. Cracow, Poland, 2008. P.283-289

we needed to get all of reference’s fields:

"authors": "Rakishev B.R.",

"title": "Open Cast Mining in Kazakhstan Under Market Conditions.",

"journal": "//The 21st World Mining Congress & Expo 2008. New Challenges and Visions for Mining.",

"location": "Cracow, Poland",

"year": "2008",

"pages": "P.283-289"

Since references have different ways of formatting, we need more than a bunch of “if”s and mighty regexp tricks to accomplish it. This is where machine learning algorithms come in handy.

In this article I’m going to show you an algorithm of extracting such metadata using hidden Markov model.

Hidden Markov model

First, we need to learn some theory behind the method.

Imagine a process which can be in one of its possible states. As time passes by, the process may transition from one state to another with given probabilities (the sum of probabilities to all possible states is 1). During transition, the process emits the so called “output symbol” (or observable output) which is an abstract thing and depends on the nature of the process being modeled. Each symbol has an emission probability and total sum of emission probabilities of all possible symbols from a state equals to 1. The process also has one important property, called “Markov property”: the future of the process (i.e. its future state) depends only on the present state.

Now suppose we are observing such process, but we can’t see the states and transitions. Instead, we see only output symbols which are being emitted as process transitions between states. Such process is called hidden Markov model, or HMM for short. It is called hidden because states are invisible to observer, only output symbols can be seen.

HMM has many applications in modern software, for example speech recognition systems are based on HMM. Speech is divided into short-time (10 ms) signals which can be seen as output symbols. Text is considered to be the “hidden cause” of speech. HMM allows to find most likely text that caused this sequence of audio signals.

Other fields where people have been succesfully using HMM include include machine translation, gene prediction, cryptanalysis and many other things.

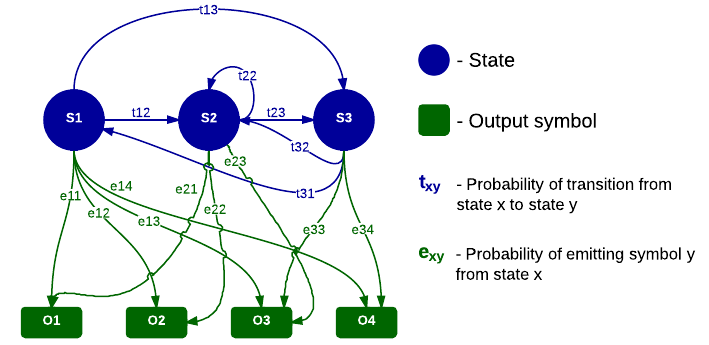

This is a simple diagram showcasing different parameters of HMM:

Summarizing everything, HMM can be specified by the following parameters:

- Set of possible states

- Set of possible output symbols

- Start probabilities (probability of being in one of the states initially)

- Probabilities of transitions between any two states

- Probabilities of symbol emissions from each state

We will be solving the following problem: Given HMM specified by aforementioned parameters and a sequence of output symbols, find a most likely sequence of states that led to such output sequence.

Building our model

We can see the process of forming of a string of reference as a HMM. Each reference field can be mapped to two states. So, in order to come up with a set of states we must first decide which reference fields we’d want to capture. Here are the fields I used: author, title, date, pages, volume, journal, number, url, publisher, location. We could have treated each of this fields as a separate state, but as noted in [1], using multiple states per field leads to better results, so I decided to use 2 states per field: a “start” state and an “rest” state. Say, for author field, we’d have 2 states: “author start” and “author rest”.

We must also specify set of symbols. In our case, any symbol corresponds to a set of strings, because state transitions happen by emitting strings. It would be impractical to map one symbol to just one string, instead we map one symbol to a set of strings defined by a regular expression. For example:

-

symbol “uppercase word” is defined by regular expression

\p{Lu}+. Note that this regular expression uses Unicode character properties -

symbol “pages” is defined by

p(ages?)?|pp|с(тр)?. References may be written not only in English but also in Russian and Kazakh, so this regexp can capture ‘pages’ as well as its equivalents in Russian – ‘с.’ and ‘стр.’ -

symbol “semicolon” is defined by

:

You might ask “can’t we just throw a random regexp, say \w{2}\d+, and call

it the way we’d like to?”. However, to improve the quality of parsing, it only

makes sense to choose the most common types of strings encountered in

references. For example, author names are always formed of one title case word

(“Pivovarova”) and one or more letters for initial (“T. I.”). Years are almost

always given as four-digit string. Double slash “//” usually precedes the name

of journal or magazine. So these strings are good examples of separate symbols.

After doing some research of available references, I compiled the following set of symbols and their corresponding regular expressions:

protected $symbolRegexps = array(

'comma' => ',',

'dot' => '\.',

'hyphen' => '[\-—–]',

'colon' => ':',

'semicolon' => ';',

'question' => '\?',

'quote' => '"',

'leftParen' => '\(',

'rightParen' => '\)',

'leftBracket' => '\[',

'rightBracket' => '\]',

'openQuote' => '«',

'closeQuote' => '»',

'slash' => '\/',

'misc' => '[_\*&\^%]',

'apostrophe' => "'",

'number' => 'no|num(ber)?|№|номер',

'volume' => 'vol|т(ом)?',

'pages' => 'p(ages?)?|pp|с(тр)?',

'press' => 'изд(ательство)?|press',

'release' => 'вып(уск)?',

'protocol' => 'https?|ftp',

'other' => 'др(угие)?',

'upperLetter' => '\p{Lu}',

'lowerLetter' => '\p{Ll}',

'upperWord' => '\p{Lu}+',

'titleWord' => '\p{Lu}\p{Ll}+',

'fourDigit' => '\d{4}',

'digit' => '\d+',

'word' => '\p{L}+',

);Choosing a correct set of symbols is said to be crucial for algorithm’s quality and performance, so experimenting with and tweaking it might be a good idea.

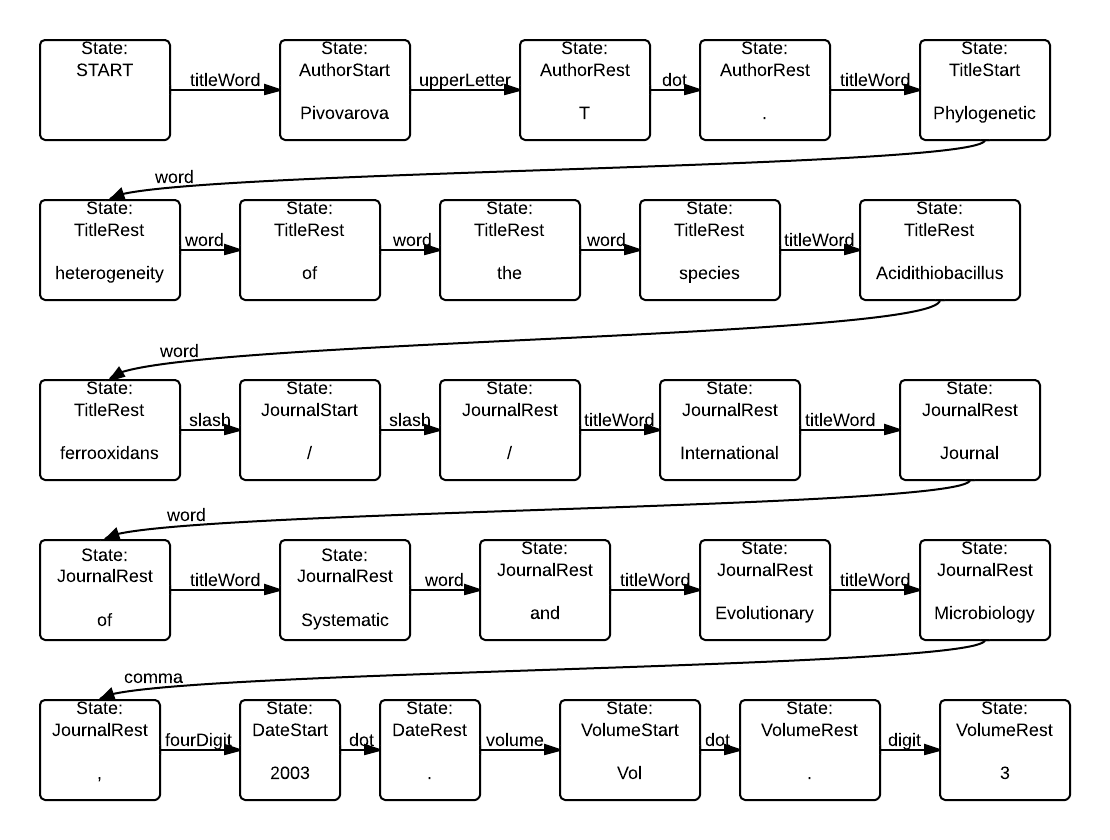

Suppose we have this reference string: Pivovarova T. Phylogenetic heterogeneity of the species Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans // International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2003. Vol. 3. Then modeling the process would look like this:

Boxes represent states, arrows represent transitions and symbols being emitted. Note, however, that states are hidden initially, because we can only see output symbols.

Training

Training phase is present in many machine-learning algorithms and this method is no exception. Essentially, training means setting up good parameters for underlying model or algorithm. Our model needs these parameters in the form of transition and emission probabilities. Where do we get these parameters? The answer is simple – by training on real data. To do it, we must take real data, i.e. list of real references and manually tag each field. It’s like a human acting as a teacher for the model. The more data, the better.

My friend did this boring part in a few days, tagging everything this way:

<A>Dostanova S.<T>The modern state of theory and methods of calculation of the

thin-walled spatial constructions and way of their development. Kazakhstan/s

Economy. The Global Challenges of Development.<V>Volume II.

ICET.<D>2012.<P>65-67p

Basically, <X> something <Y> another means “something” lies in state X and

“another” is in state Y.

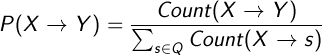

The probability of making a transition from state X to state Y is the ratio of the number of transitions made from X to Y to the total number of transitions from X:

where Q represents set of states.

Emission probabilities are computed the same way: the probability of emitting a symbol Y at state X is the ratio of the number of times Y is emitted at X to the total number of emissions of Y.

I wrote a script to parse tagged references, which does the following things:

- splits each reference into substrings by state boundaries

- converts each substring into a sequence of symbols

- counts state transitions and symbol emissions for each state

After this, we’ll have all necessary numbers to calculate probabilities and build probability matrices. After computing them, they must be persisted to somewhere like configuration file.

Smoothing

Actually, we haven’t done with training yet. See, our training may not cover

EVERY possible transition or emission that may happen in the real-world data.

I set probability of such events to some low constant and then substracted this

amount from probabilities of non-zero events to keep the sums equal to 1. For

example, if we have Z events with zero probability, and NZ events with non-zero

probability in training data, we substract Z * C / NZ from probabilities of

all events with non-zero probabilites.

Algorithm

Algorithm of extracting reference’s fields consists of following steps:

-

Split the string representing a reference into tokens separated by spaces and punctuation marks, capturing each punctuation mark as an individual token.

-

Map each obtained token to a symbol by trying to match regular expressions one by one. After this step, we’ll have sequence of symbols.

-

Now it is time to find the most likely sequence of states which led to a sequence of symbols obtained in previous step. Luckily, algorithm for this problem has already been invented in 1967 by engineer Andrew Viterbi and is called The Viterbi algorithm. The Viterbi algorithm accepts several parameters - sequence of symbols, set of states, set of symbols, probability matrices obtained from training, and, using dynamic programming approach, finds the most likely sequence of states. The Wikipedia page has implementations of the algorithm in Python and pseudocode, I looked at them to implement it in PHP.

-

After getting sequence of states, find a list of corresponding tokens for each state and join them together with whitespace between them to obtain reference’s individual fields.

Results

This isn’t directly related to HMM method, but references had to be extracted

from PDF files. pdftotext and a bit of regexp magic accomplished this task

easily. After processing 3000 or so PDF files, we took a look at a small subset

of references, and roughly 90% of them were converted succesfully.

Furthermore, we integrated it with the PDF uploading form, so any badly converted references could be fixed at that moment by hand.

Conclusion

In this article I presented a method of extracting reference metadata using Hidden Markov models. It was quite interesting actually. If you have never heard of or used machine-learning algorithms I encourage you to read about and maybe even try some, they are very useful :)

I have uploaded the source code of extractor (it’s PHP btw) to github: https://github.com/redcapital/reference-parser

References

-

Seymore, Kristie and Rosenfield, Roni, “Learning Hidden Markov Model Structure for Information Extraction” (1999). Computer Science Department. Paper 1325. http://repository.cmu.edu/compsci/1325

-

Ping Yin , Ming Zhang , Zhihong Deng , Dongqing Yang “Metadata Extraction from Bibliographies Using Bigram HMM”. ICADL 2004, LNCS 3334, pp. 310–319, 2004.